VOA Broadcasts in Russian from Munich – A Backstory

By Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum and Voice of America – Hidden History

The Information Bulletin of the Office of the US High Commissioner for Germany had a short report in its June 1952 issue on the Voice of America (VOA) Russian-language broadcasts originating from Munich, West Germany, from what was called the European Radio Center. 1 The newly-established Radio Free Europe (RFE) was also based in Munich. However, the RFE operation, then still secretly-funded and secretly managed by the CIA while presented to the public as an entirely private initiative funded by private donations, was not at least officially linked with the US government. The Voice of America, established in 1942 by the Roosevelt Administration during World War II to produce anti-Axis propaganda and broadcast war news, was officially a U.S. government-run radio station operating since 1945 within the US State Department. VOA’s headquarters in 1952 were in New York City.

The short article about the Voice of America on page 18 of the Information Bulletin was titled “VOA Broadcasts in Russian from Munich,” but it also included information about VOA Lithuanian and VOA Polish broadcasts originating from West Germany. The article noted that the United States government did not recognize the forceful annexation of Lithuania in 1940 by the Soviet Union. The US government also did not recognize the Soviet annexation of Latvia and Estonia and maintained diplomatic relations with the pre-war governments-in-exile of all three Baltic States. Washington, however, had diplomatic relations with Poland and other Soviet Block countries in East-Central Europe.

“VOA Broadcasts in Russian From Munich,” Information Bulletin, The Office of US High Commissioner for Germany, June 1952. Page 18.

VOA Broadcasts in Russian from Munich

THIS IS the Voice of America speaking to you from Europe” is heard nightly in Russian. Commencing May 22, the Voice of America launched its first Russian language program to originate from western Europe.

The program, prepared and broadcast from VOA’s European Radio Center in Munich, is heard from 10 to 10:15 p.m., Central European Time, or midnight to 12:15 a.m., Moscow Time. It brings to Soviet listeners the voices of their own people who have taken the road to freedom, and also sends behind the “Iron Curtain” news and information suppressed or distorted by the Soviet Government.

The new Russian program follows closely the inauguration of the Lithuanian-language program, now heard daily from 7:45 to 8 p.m. Central European Time. It went on the air (or the first time May 15 – the 32nd anniversary of the opening of the Lithuanian parliament. That parliament reaffirmed the independence of the Lithuanian Republic and adopted its constitution. Although forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union in 1940, Lithuania continues to be recognized as a sister republic of the United States of America and other free countries.

THE LAUNCHING of the Lithuanian and Russian programs was undertaken after careful testing of the pilot project of VOA broadcasting from Europe, which began with the Polish program Oct. 1, 1951. Effectiveness of the Polish broadcast became apparent through the. attacks of Polish press and radio on VOA, and from reports of Polish fugitives who say that VOA was an important influence in their decision to flee the country.

Headed by a few hand-picked American experts on Iron Curtain areas, the European Radio Center of the Voice of America has hired security-tested refugees. These men and women have recent first-hand knowledge of conditions inside captive countries. Many have survived harrowing experiences in forced labor camps and prisons.

TYPICAL OF these is Marian Czuchnowski, writer, poet and journalist on the Polish staff in Munich.

After the defeat of the Polish army by the German army in 1939, Czuchnowski was arrested by the Red army while fleeing the Nazis, He underwent a year of grilling, transfers, interrogations and then a three-year forced labor sentence. He survived typhus and pneumonia before he was released and joined the Polish government in exile.

Returning to Poland after the war, Czuchnowski went underground when the Soviet-puppet Lublin government took over the country, The “shadow government” dissolved in 1948 and Czuchnowski returned to free-lance journalism. He joined the staff of VOA in November, 1951.

The Backstory

The VOA Munich Center was a relatively new and small scale project of the Truman Administration to show that the United States government was serious about reforming its international broadcasting and countering communist propaganda. After several years of ignoring repressions and human rights violations in the Soviet Union and in East-Central Europe, by 1952 the new policy of the Voice of America management in the US State Department was to establish presence closer to the target area to be able to provide more local news and commentary with the help of refugee journalists and escapees from the Soviet Block countries. The first VOA broadcast from Munich was in Polish on October 1, 1951. In moving a small part of its operations to Munich, VOA was duplicating to a limited degree the highly desired and successful RFE model of surrogate broadcasting consisting of using first-hand sources of information from the target countries.

The Information Bulletin article said that the VOA Center in Munich was headed by “a few hand-picked American experts on Iron Curtain areas” and that it “has hired security-tested refugees.”

Security was an important issue for the Truman Administration and the US Congress after much criticism that the Roosevelt Administration had hired broadcasters to work for the Voice of America who were Soviet sympathizers and in some cases Communist Party members. One of the Polish broadcasters employed in Munich in the early 1950s later turned out to be a spy for the communist regime in Warsaw and defected back to Poland, but he was a minor figure who did not have a programming policy or editing role. Other VOA journalists in Munich were solidly anti-communist refugees.

The article noted that the men and women hired to work at the Munich Center had “recent first-hand knowledge of conditions inside captive countries” and that many had “survived harrowing experiences in forced labor camps and prisons.” This was another indicator of a major change in Voice of America hiring and programming policy because during World War II and for several years after the war VOA remained silent about Stalin’s crimes and refugees fleeing from the Soviet Block countries.

Many of the early VOA officials and broadcasters in New York were strong supporters of Soviet Russia. Some of the VOA Polish Service broadcasters who had worked in New York during the war and in some cases for a few years after the war later went back to Poland and became propagandists for the communist regime in Warsaw. 2 Perhaps in an effort to show that such individuals were no longer employed by the US government, the 1952 article described briefly the story of a Polish anti-communist refugee who was a former prisoner in the Soviet Gulag and was hired in Europe by the Voice of America. His name was Marian Czuchnowski. He was a writer, poet and journalist working on the VOA Polish desk in Munich.

The monthly Information Bulletin magazine was published in Frankfurt by the Office of Public Affairs of the High Commission for Occupied Germany (HICOG). Its purpose was described as providing “the dissemination of authoritative information concerning the policies, regulations, instructions, operations and activities of the United States mission in Germany.” The U.S. State Department seal was printed on the bulletin’s cover page. The Allied High Commission (also known as the High Commission for Occupied Germany – HICOG) was established in 1949 by the United States, the United Kingdom and France to oversee the political development of the Federal Republic of Germany and ceased to exist in 1955. The US High Commissioner in June 1952 was John J. McCloy, a US government official, lawyer, diplomat, banker and an advisor to US presidents from Franklin D. Roosevelt to Ronald Reagan. As US High Commissioner for Germany, McCloy supported the establishment of Radio Free Europe facilities in West Germany. 3

The article in the June 1952 Information Bulletin confirms that the US office of the High Commissioner was also supportive of increased presence of Voice of America in West Germany. The establishment of the VOA Munich News Center was one of the responses of the Truman Administration to Stalinist repressions. The October 1951 issue of the Information Bulletin from the office of US High Commissioner for Germany quoted Maximilian Jiri Lom, a Czechoslovak communist government official who had escaped to West Germany. He described Czechoslovakia under communism as a concentration camp, telling Western reporters at a press conference in Frankfurt on September 27, 1951, “”you cannot imagine how desperate life in this big concentration camp, called Czechoslovakia, is today.” 4 Before 1951, the Voice of America would not broadcast such criticism of the Soviet Union and other communist regimes. Toward the end and immediately after World War II, VOA supported the establishment of pro-Soviet governments in the region. VOA also presented Stalin as a statesman who would guarantee freedom and democracy in post-war Europe. 5

As a result of criticism in the US Congress and President Truman’s own “Campaign of Truth” initiative, the Voice of America switched in the early 1950s from supporting Soviet plans for Eastern Europe and covering up communist crimes to exposing them and countering Soviet propaganda. Some of this information can be found in the 1952 article but without references to the earlier Voice of America’s propaganda collusion with Stalin’s Russia during World War II, which extended to some degree into several years after the war under State Department officials and VOA journalists who were sympathetic to the Soviet Union or did not want to upset diplomatic relations between Washington and Moscow.

The article also did not explain the reasons for the highly surprising lack of VOA broadcasts in Russian until 1947. It can be assumed that pro-Soviet Roosevelt Administration officials, who secretly coordinated Voice of America propaganda with Soviet propaganda, were afraid that VOA broadcasts in Russian during the war could upset Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. 6

The “Campaign of Truth” was President Truman’s multi-faceted US government’s international information policy unveiled by him in a foreign policy speech on April, 20, 1950 to members of the American Society of Newspaper Editors as the answer to harsh Soviet propaganda attacks on the United States and its allies. 7

VOA eventually sharpened its program content and tone after much prodding and criticism in the US Congress and media but not without some initial resistance and a considerable delay. The resistance was far from universal. Some at VOA, especially among native-born Americans hired during the Roosevelt Administration, did not approve of a harder stance against Russia; others, especially recent refugees from Fascism and Communism who knew from their own experience that the two totalitarianism shared much in common in their disdain for freedom and human rights, cheered and lobbied for a change of programming.

The Voice of America, New York QSL postcard, 1949. From 1942 until 1954 VOA headquarters were in New York City. In 1954, VOA was moved from New York to Washington, D.C.

The Truman White House was not happy with Voice of America programs after widespread criticism that they were soft on communism and the Soviets. According to Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., who had worked for VOA as an English-language writer-producer and later compared VOA programs in 1947 with those in 1950-1953, VOA’s first Russian-language broadcast did not include outside of the newscast any criticism of Soviet leaders or an analysis of human rights issues under communism. Helwick also observed that mainstream U.S. media outlets were also not impressed with the direction and tone of the first VOA Russian broadcast from New York in February 1947.

It was evident from newspaper accounts that the broadcast in America, at least, was received with something less than enthusiasm. Typical of the reactions the New York World Telegraph headline, “Russians Restrain Joy over U.S. Broadcast.” 8

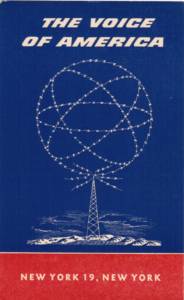

Charles Thayer, the State Department Foreign Service Officer put in charge of launching VOA Russian broadcasts in February 1947 and later VOA director, was apparently deceived by Soviet propaganda and believed the Kremlin’s lies designed to absolve Stalin for his responsibility for mass murders. 9 Thayer was forced later to resign from the Foreign Service. Early VOA Russian broadcasters, many of whom were anti-communist, were not allowed to criticize the Soviet Union when Thayer was in charge of the Russian Service. One of them, Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson (1913-2002), noted this in her memoir published in 1994.

Voice of America Russian Service broadcaster Helen Zhemchuzhny Bates Yakobson. The sign on the microphone says: “The Voice of the United States of America.” The photograph was used in a 1952 US State Department promotional pamphlet.

In those early years, VOA programs attempted to give full and impartial reports of life in the United States, including confessions of our shortcomings and faults. No direct criticism or attacks on the Soviet system were permitted. After all, they had only recently been our allies. But as the Cold War intensified, VOA responded and became openly and vigorously critical of the Soviet system and government. 10

“Radio Broadcast Sent To Russia By State Department” photograph from the National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Description: Interior view of seven men and women taken during a radio broadcast sent to Russia from the State Department’s studios in New York. Identified as left to right: Boris Brodenov, Kathrine Elene, James Shigorin, Vladmir Postman, Mrs. Lucy Bates, Victor Franzusoff, and Mrs. Tatiana Hecker, all American citizens. Lettering on top of microphone is in Russian language. (Charles Thayer supervised the programs.) Date(s): ca. February 1947.

The later head of the VOA Russian Branch, a pre-World War II Soviet defector Alexander Gregory Barmine, a former Red Army general, was strongly anti-communist. He told the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, chaired by Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI), otherwise infamous for making many false accusations of communist influence within the US government, that he received instructions to play down the anti-Semitism of the Soviets. 11 The Truman Administration later removed such restrictions. The Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, while highly critical of the earlier management of the Voice of America in the State Department concluded in 1954 that some VOA scripts “particularly those from branches under the direction of such knowledgeable anti-Communists as Alexander Barmine of the Russian Division and Gerald F. P. Dooher of the Near East, South Asian Division, were most impressive.” 12 Such a conclusion would not have been possible from a highly anti-communist Senate subcommittee if the Truman Administration did not initiate managerial and programming reforms at the Voice of America.

After President Truman’s “Campaign of Truth” speech, Secretary of State Dean Acheson said in his semiannual report to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program for the period July 1 to December 31, 1950, that “Operationally, launching of the Campaign of Truth was reflected at the outset more in sharpened program content and specialized radio treatment than in marked increases in broadcast operations.” 13 Acheson indirectly agreed with critics that earlier VOA programming to the Soviet Union was not well-planned to meet the Soviet propaganda challenge. Jamming was not the main factor for the need to change VOA’s programming policy. The Stalinist regime was just as murderous in 1947, when the VOA Russian broadcast was finally started, as it was in the second half of 1950, the period covered by Acheson’s report to Congress.

In the broadcasts to Eastern Europe, greater program variety was introduced; more liberal use was made of anti-Communist political satires and exposés, and of the documentary and dramatized technique.

The systematic jamming of VOA’s Russian broadcasts greatly influenced both their content and format. Music and dramatizations were eliminated, and the salient portions of the programs were repeated around the clock. Later in the period, when a partial neutralization of the Soviet jamming effort was achieved, some of the dramatized material was restored. An increasing number of Soviet DP’s came to the microphones of VOA to tell their story. 14

At least, Secretary Acheson admitted that VOA’s program content was previously not sufficiently sharp, but progress to fix the problem was not quick within the government bureaucracy. Whistleblowers and members of Congress continued to report questionable programming at VOA for at least two more years. 15 The Voice of America improved its radio broadcasts to the Soviet Block later in the 1950s but did not expand them substantially, except for Russian-language programs. Even adding extra time to VOA Russian broadcasts took several years since their inception in 1947.

Millions of dollars went toward building new radio transmitters but there were no spectacular new VOA programming initiatives targeting the Soviet Block. Secretary Acheson was able, however, to report to Congress in 1952 on new “program originations within the shadow of the Iron Curtain from the new Munich programming center with a daily Polish-language broadcast.” 16 These were modest additions although with substantially improved reporting on human rights violations behind the Iron Curtain. It was far less than what was needed and what audiences wanted from VOA. The new VOA program to Poland from Munich was only 15 minutes long. It was later expanded to 30 minutes. The Polish Service also had a 15-minute morning program and a 30-minute evening program originating from New York.

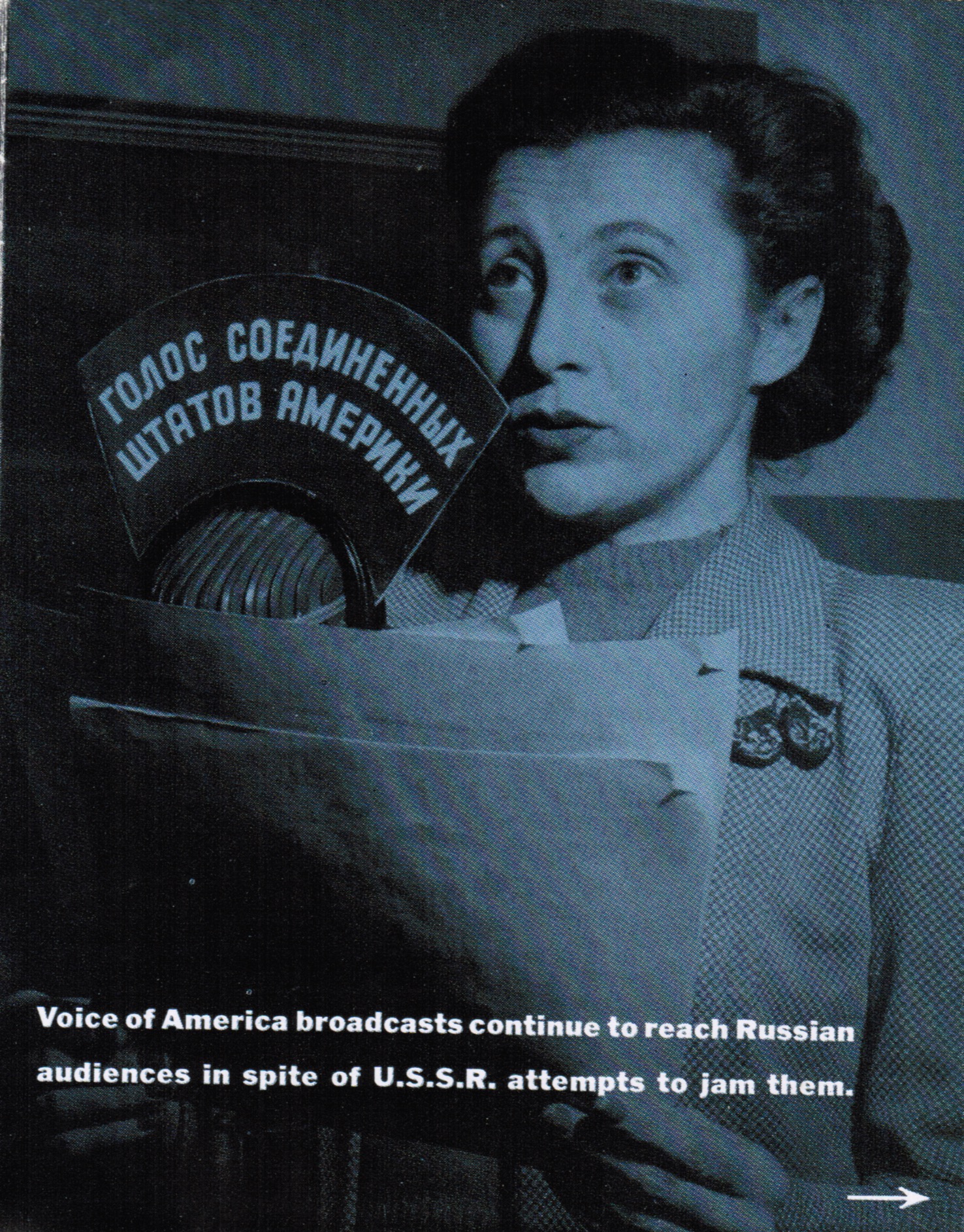

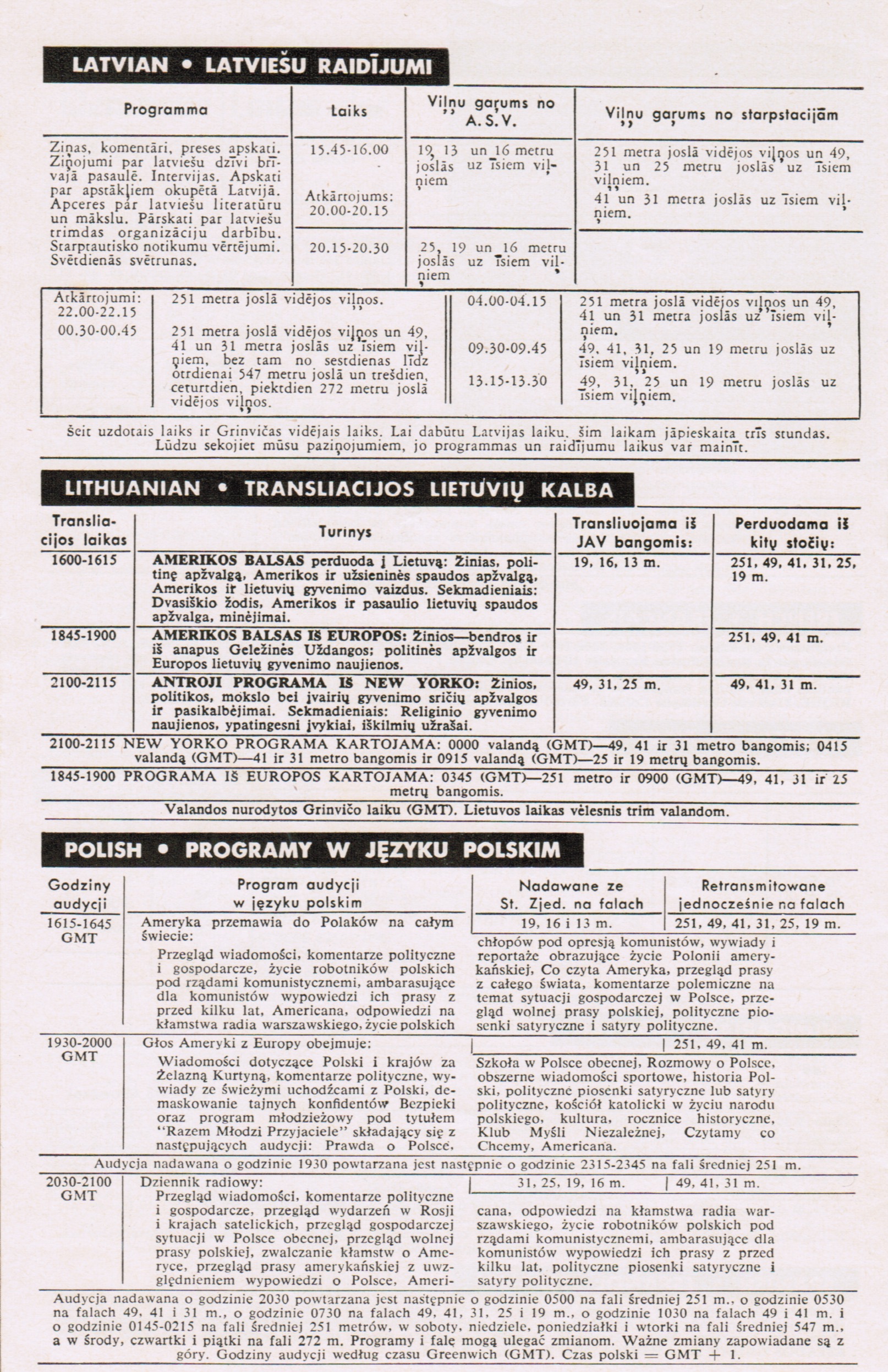

The special Russian-language European program of the Voice of America broadcast from Munich was still only 15 minutes long in January 1953, according to a program schedule printed in one of VOA’s promotional brochures. The Russian-language program schedule for January-February 1953 did not list individual programs for the Russian broadcast originating from Munich. The Lithuanian program schedule noted the special broadcast from Munich but also did not list individual programs. The Polish program schedule listed individual programs from the VOA European Program Center in some detail. It was clear that the 30-minute Polish-language broadcast from Munich had all the characteristics of surrogate radio programs such as those produced many hours daily by Radio Free Europe, also from Munich.

Voice of America from Europe includes:

News relating to Poland and countries behind the Iron Curtain, political commentaries, interviews with recent refugees from Poland, unmasking of secret Bezpieka [Polish communist secret police] informants, and the youth program titled: “Razem Młodzi Przyjaciele” (“Together Young Friends”) consisting of following shows: Truth About Poland, Schools in Today’s Poland, Conversations About Poland, extensive Sports News, Polish History, Political Satirical Songs or Political Satire, Catholic Church in the Life of the Polish Nation, Culture, Historical Anniversaries, Club of Independent Thought, We Read What We Want, Americana.

VOA Russian broadcasts listed in “Die Stimme Amerikas” German Service January-February 1953 promotional pamphlet.

VOA Latvian, Lithuanian, and Polish broadcasts listed in “Die Stimme Amerikas” German Service, January-February 1953 promotional pamphlet.

The Voice of America center in Munich opened in late 1951 and eventually included VOA broadcasters from several countries who initiated short programs based partly on interviews with refugees from behind the Iron Curtain in an apparent attempt to compete with Radio Free Europe which had much more airtime and more relevant news. One of VOA’s broadcasters in Munich, Zbigniew Brydak (aka Stefan Michalski), turned out to be a Polish communist spy. RFE refused to hire him but he briefly worked for VOA as a commentator and announcer. Brydak did not have any editorial or managerial functions at the Voice of America in Munich, but before coming to West Germany he was, according to former RFE/RL journalist and former VOA Polish Service deputy chief Marek Walicki who knew him, an agent-provocateur for the communist regime who denounced a number of young Poles to the communist secret police who were then tortured and executed. Brydak later returned to Poland and joined a former Voice of America editor Stefan Arski (aka Artur Salman) in writing articles and producing anti-U.S. propaganda broadcasts. 17

Arski was one of many pro-communist wartime VOA journalists, including VOA’s first chief English-language news writer and editor Howard Fast, a best-selling American author who in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize. 18 Arski, whose legal name at the Voice of America was Artur Salman, remained in his VOA job being employed by the State Department until 1947.

Unlike Brydak at the VOA Munich Center, Arski had some managerial and editorial role in New York during and after the war in shaping VOA programs to Poland. 19

President Dwight Eisenhower later wrote about Arski’s bosses that because of their pro-Soviet zeal, some of these early Voice of America officials were insubordinate toward President Roosevelt who himself was pro-Soviet but not nearly as much his propagandists in the Office of War Information (OWI) which was in charge of wartime VOA broadcasts. 20 They included the first Voice of America Director John Houseman who was forced by the State Department to resign from VOA in 1943. In 1945, Houseman tried to get reemployed by the post-war US administration in Germany. His attempt to get a new US government job was again blocked for security reasons. He later had a very successful career as a Hollywood actor . 21

Oswego, New York. Howard Fast, author of “Citizen Tom Paine,” addressing high school students, June 1943. United Nations flags are on the stage during United Nations week. Collins, Marjory, 1912-1985, photographer. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540. Fast worked at the Voice of America until 1944. He was later an activist in the Communist Party USA, reporter and editor for the party’s newspaper, and the 1953 recipient of the Stalin International Peace Prize.

Office of War Information (OWI) personnel record card for Artur Salman, aka Stefan Arski, who was employed by OWI from August 2, 1943 and continued his employment as language editor and radio script writer (Polish) for the Voice of America (VOA) in the U.S. State Department until February 15, 1947.

The Voice of America was not able to compete in surrogate broadcasting with Radio Free Europe which had more airtime, many more sources of information and better management than VOA. In most countries in East-Central Europe, including Poland, RFE had much larger audiences than VOA. In Russia, the VOA Russian Branch managed to keep up in audience popularity with Radio Liberty’s Russian Service for most of the Cold War period, at least according to audience surveys conducted by the US government among travelers from the Soviet Union to the West. With VOA’s weaker performance in Eastern Europe and the start of the US policy of engagement with the Soviet Union, the VOA Munich Center was closed after operating for eight years but Radio Free Europe continued its broadcasts from Munich until 1995 when the combined Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (RFE/RL) moved its headquarters from Germany to Prague in the Czech Republic.

Notes:

- Information Bulletin Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the U.S. High Commissioner for Germany, Office of Public Affairs, Information Division, APO 757-A, U.S. Army, June 1952, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.omg1952June. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Mira Złotowska – Michałowska — pro-Soviet Propagandist at OWI and VOA,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), December 10, 2019, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/mira-zlotowska-michalowska-pro-soviet-propagandist-at-owi-and-voa/. Mira Złotowska, later known as Mira Michałowska who published books and articles in English as Mira Michal and used several other pen names, was one of many radically left-wing journalists who during World War II worked in New York on Voice of America (VOA) U.S. government anti-Nazi radio broadcasts but also helping to spread Soviet propaganda and censoring news about Stalin’s atrocities. While not the most important among pro-Soviet propagandists at the Voice of America during the war, Michałowska later went back to Poland, married a high-level communist diplomat and for many years supported the regime in Warsaw with soft propaganda in the West while also helping to expose Polish readers to American culture through her magazine articles and translations of American authors. One of the American writers she translated was her former VOA colleague and friend, the 1953 Stalin Peace Prize winner Howard Fast who in 1943 played an important role as VOA’s chief news writer. Despite today’s Russian attempts to undermine journalism with disinformation, the Voice of America has never officially acknowledged its mistakes in allowing pro-Soviet propagandists to take control of its programs for several years during World War II. Eventually, under pressure from congressional and other critics, the Voice of America was reformed in the early 1950s and made a contribution to the fall of communism in East-Central Europe. ↩

- Richard H. Cummings, Radio Free Europe’s “Crusade for Freedom”: Rallying Americans behind Cold War Broadcasting, 1950-1960 (Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co, 2010), p. 22. ↩

- Information Bulletin, Frankfurt, Germany: Office of the US High Commissioner for Germany Office of Public Affairs, Public Relations Division, APO 757, US Army, October 1951, http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/History.omg1951Oct. ↩

- Sandro Gerbi, “Italy and the Voice of America” (Columbia University: Centro Primo Levi New York, 2010), https://primolevicenter.org/italy-and-the-voice-of-america/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director Was a Pro-Soviet Communist Sympathizer, State Dept. Warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. ↩

- Harry S. Truman, “Address on Foreign Policy at a Luncheon of the American Society of Newspaper Editors,” April 20, 1950. National Archives, Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/library/public-papers/92/address-foreign-policy-luncheon-american-society-newspaper-editors. ↩

- Edward Carleton Helwick, Jr., “Policy problems of the Voice of America: 1945-1953.” Master Thesis, Department of Political Sciences, University of Southern California, June 1954, pp. 218-219. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Secret Memos on How Voice of America Was Duped by Soviet Propaganda on Katyn Massacre,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 2, 2021, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/secret-memos-on-how-voice-of-america-was-duped-by-soviet-propaganda-on-katyn-massacre/. ↩

- Helen Yakobson, Crossing Borders: From Revolutionary Russia to China to America (Tenafly, N.J: Hermitage Publishers, 1994), 146. ↩

- Voice of America: Report of the Committee on Government Operations Made By Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954, p. 9. ↩

- Voice of America: Report of the Committee on Government Operations Made By Its Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1954, p. 5. ↩

- Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 3. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=8. ↩

- Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Sixth Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1950,” Department of State Publication 3479, December 1951, p. 4. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562370p?urlappend=%3Bseq=11. ↩

- “Voice of America 1951 – ‘Drab’ ‘Unconvincing,’” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), February 24, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/2018/02/23/voice-of-america-1951-drab-and-unconvincing-rep.-wiggleswoth-quotes-listeners-in-poland/. ↩

- Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State, “Launching the Campaign of Truth–First Phase: Eight Semiannual Report of the Secretary of State to Congress on the International Information and Educational Exchange Program, July 1 to December 31, 1951,” Department of State Publication 4575, December 1951, p. 1. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951d03562372l?urlappend=%3Bseq=6. ↩

- See in Polish Marek Walicki’s Z Polski Ludowej do Wolnej Europy (Warszawa: Bellona, 2018), pp. 170-182. RFE had several more communist agents working for them, also usually in minor positions without any significant editorial influence. Communist regimes perceived the two stations as much more dangerous to them than VOA and concentrated their spying activities on them. ↩

- Cold War Radio Museum, “Created 70 years ago, Stalin Peace Prize went in 1953 to former Voice of America chief news writer Howard Fast,” December 21, 2019. https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/created-70-years-ago-today-stalin-peace-prize-went-in-1953-to-former-voice-of-america-chief-news-writer-howard-fast/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Voice of America Polish Writer Listed As His Job Reference Stalin’s KGB Agent of Influence Who Duped President Roosevelt,” Cold War Radio Museum, February 12, 2020. https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/voice-of-america-polish-editor-listed-stalins-kgb-agent-of-influence-as-job-reference/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “General Eisenhower Accused WWII VOA of ‘Insubordination,’” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 14, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/general-eisenhower-accused-wwii-voa-of-insubordination/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director Was a Pro-Soviet Communist Sympathizer, State Dept. Warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum (blog), May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. ↩

Add Comment