Ted Lipien for Cold War Radio Museum

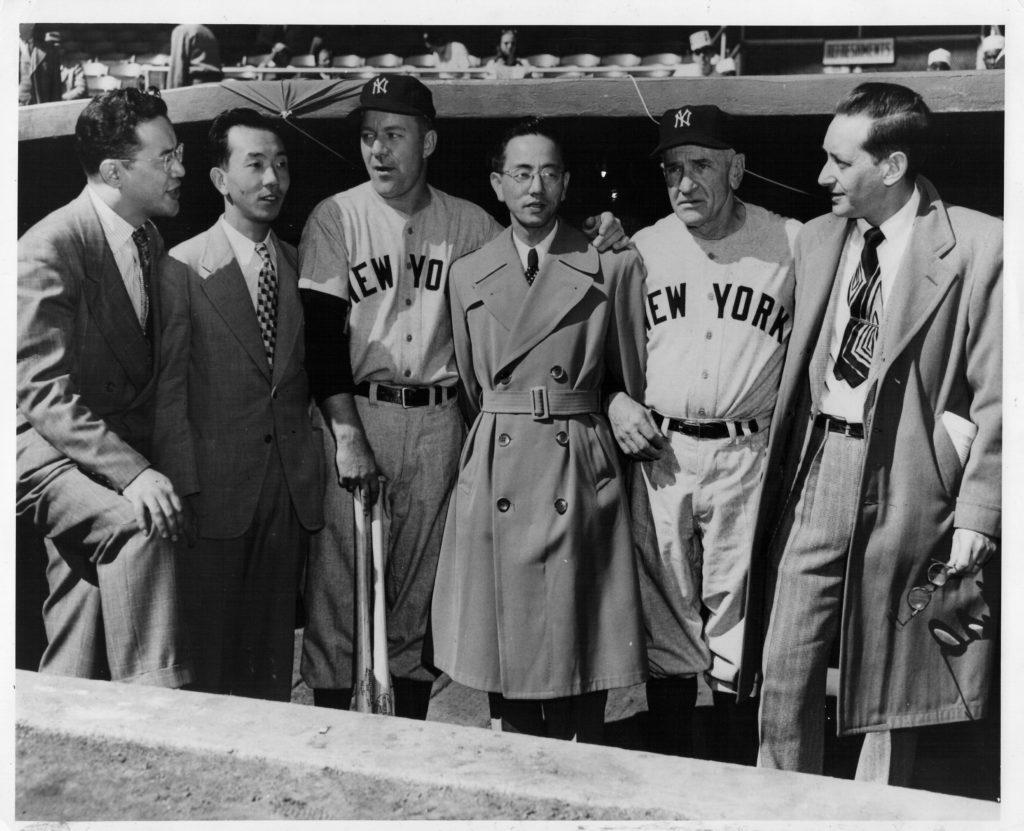

Cold War Radio Museum has acquired a press photograph showing Voice of America’s (VOA) Japanese Service sportscasters with New York Yankees baseball team pitcher Eddie Lopat and team manager Casey Stengel. The photograph is of an undetermined origin but may have been distributed by the Voice of America to U.S. newspapers and magazines for reporting and publicity purposes. The photo was taken circa 1950 when VOA still produced radio broadcasts in Japanese.

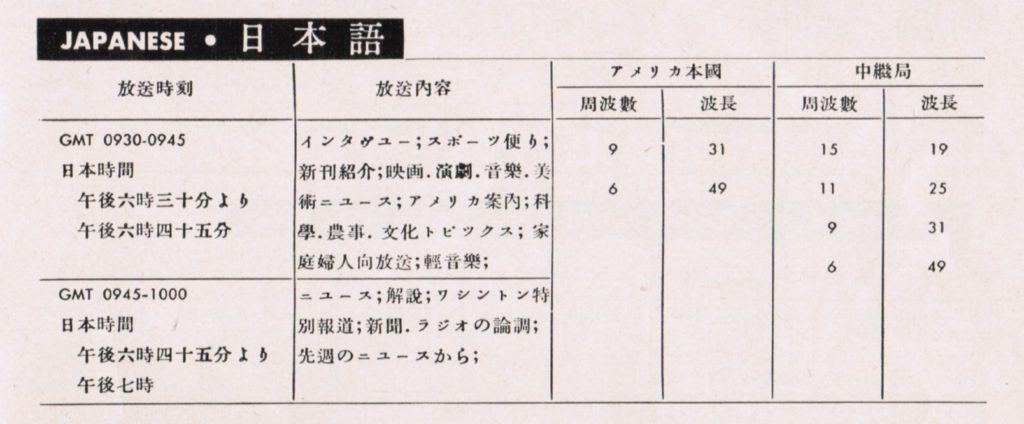

The Voice of America Japanese Service was established in 1942 during World War II shortly after the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. It produced shortwave radio broadcasts until the end of the war but was eliminated when President Truman abolished Voice of America’s parent agency, the Office of War Information (OWI), in 1945 and put what remained of VOA under the State Department. VOA Japanese programs, however, were revived in 1951. They were listed in the VOA 1953 program schedule brochure.

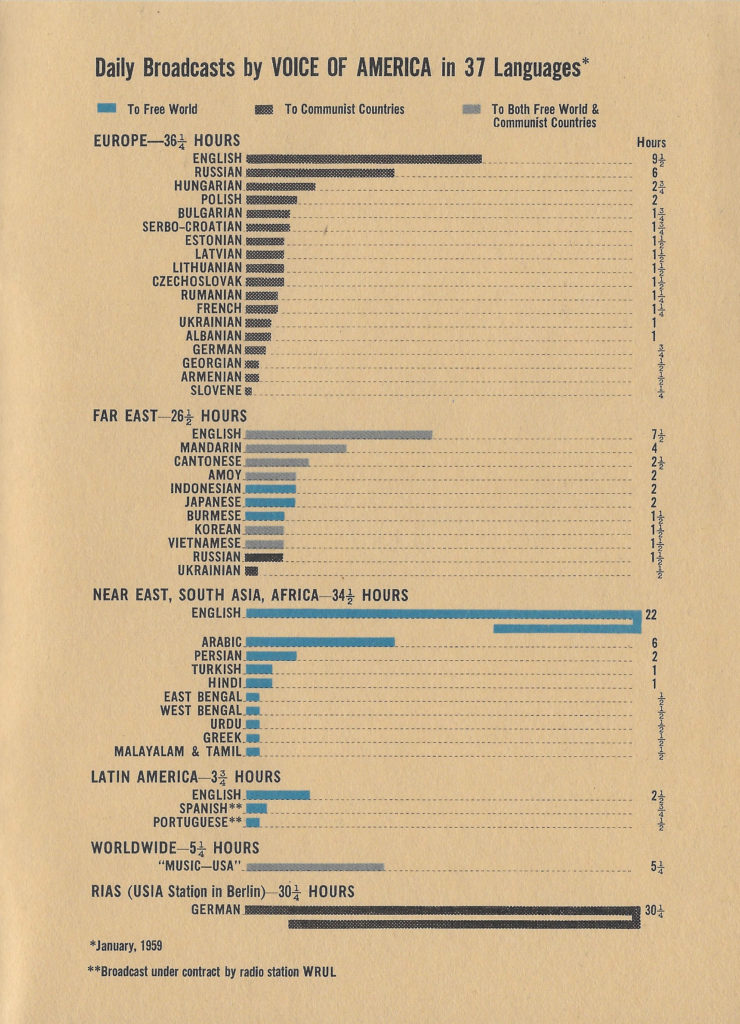

A 1959 program schedule brochure showed that Voice of America was broadcasting two hours daily to Japan. VOA Japanese programs were described as targeting “Free World.” The majority of VOA programs during the Cold War were to communist countries in Europe and Asia.

According to one eyewitness account, the most popular VOA broadcasts in Japan in the 1950s were not political programs but rather reports from World Series baseball games, as well as various music programs distributed to commercial Japanese radio stations by the United States Information Service (USIS) operating within the U.S. Embassy. [U.S. Information Agency’s (USIA) offices overseas were known as USIS (United States Information Service).] Japanese baseball fans were able to hear play-by-play commentaries in the Japanese language from World Series games thanks to cooperation between VOA and the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan (BCJ), which rebroadcast them at a convenient hour for radio listeners in Japan. Such cooperation agreements in various Free World countries were negotiated with the help of U.S. embassies.

Edmund (Eddie) Walter Lopat (originally Lopatynski), a Major League Baseball pitcher who appears in the press photograph acquired by Cold War Radio Museum, was traded to the New York Yankees in 1948. Charles Dillon “Casey” Stengel, who also appears in the photograph with Voice of America sportscasters, was hired as New York Yankees manager in October 1948. Stengel’s Yankees won the World Series five consecutive times (1949–1953), the only time that has been achieved. It was during that period that the photograph was most likely taken. This timeframe coincides with Voice of America producing reports from American baseball games for radio stations in Japan. VOA ceased regular broadcasting to Japan in 1962.

This is how “programs for local stations” and their distribution in Free World countries were described in the 1959 Voice of America program schedule brochure:

In most of the world, local radio stations and networks are popular and attract larger listening audiences than foreign broadcasts do. In many free world countries, therefore, USIS posts [attached to U.S. Embassies] cooperate with local stations and networks to reach local listeners, in addition to broadcasts beamed from Voice transmitters.

In some areas, these local stations get direct, short wave “feeds” of news programs and coverage of special events from the United States. In other areas, local stations regularly receive “package programs” (tapes or discs consisting of news features, music, special events and interviews recorded in the studios of the Voice). Other programs are prepared by the USIS posts and are particularly effective since they can be tailored to fit the taste and specific interests of the individual country. More than 2,000 foreign stations regularly carry Voice “package programs,” and an equal number make use of locally prepared USIS radio material.

1

Henry (Hank) (Hiroharu) Gosho

The origins of the VOA baseball games transmissions to Japan are described in some detail in a 1989 interview with Henry (Hank) (Hiroharu) Gosho who was during various times of his U.S. government service a Japanese-American soldier and interpreter, a State Department Japan desk officer, a VOA Japanese Service editor on detail from the State Department, and later a United States Information Agency (USIA) public affairs officer.

As a young man, Gosho was imprisoned with his family in Minidoka detention camp for Japanese-Americans in Idaho after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. When the war started, two of his brothers were university students in Japan and later served in the Japanese army. The Minidoka War Relocation Center operated from 1942 to 1945 as one of ten camps at which Japanese Americans, both citizens and resident “aliens”, were interned during World War II. Under provisions of President Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s Executive Order 9066, all persons of Japanese ancestry were excluded from the West Coast of the United States. At its peak, Minidoka housed 9,397 Japanese Americans, predominantly from Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. While in the internment camp, Gosho volunteered in mid-August 1943 for military duty and was accepted along with 13 other Nisei, persons born in the U.S. whose parents were immigrants from Japan, because of their linguistic skills.

2He later fought against Japanese troops with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma. Merrill’s Marauders (named after General Frank Merrill), were famous for their deep-penetration missions behind Japanese lines the South-East Asian theatre of World War II.

After being wounded, Henry Gosho was evacuated to the United States and was later hired by the State Department. He transferred to the United States Information Agency after the public diplomacy agency was established by President Eisenhower in 1953.

It was somewhat ironic but not unusual in recent American history that Henry Gosho, whose illegal imprisonment together with his family and other Japanese-Americans was defended in propaganda films produced during World War II by the Office of War Information, the original parent agency of the Voice of America, later worked for OWI and its successor agency, USIA, as well as for VOA, and was the first Japanese-American hired by the State Department shortly after the war. During World War II, OWI and Voice of America also produced pro-Soviet propaganda and covered up Stalin’s crimes in the Soviet Union and communist atrocities in other countries.

3The first VOA chief news writer and editor was American Communist Howard Fast who in 1953 received the Stalin Peace Prize.

4Stalin’s mass deportations of ethnic groups served as a model for Roosevelt administration officials, including pro-Soviet propagandists working for the Office of War Information and the Voice of America who covered up the crimes associated with the Soviet Gulag—crimes incomparably greater than the internment of Japanese-Americans but not dissimilar.

5

While VOA hired new journalists

6after the war who started to broadcast truthful news about the Soviet Union and communism, justice for Japanese-Americans was not fully served until 1988 when President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act. The legislation included a formal apology to Japanese-Americans and put into place a system of reparations to living survivors of the camps. The U.S. government’s actions are described as a “grave injustice” that was “motivated largely by racial prejudice, wartime hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.”

Henry Gosho’s bio on the Marauder.org website mentions that in addition to his military service during World War II, Henry Gosho later worked briefly for the Office of War Information although it is not clear in what capacity.

Henry was one of the men that volunteered to join the Military Intelligence Service Language School from one of the West Coast Internment Centers. Henry got his nickname Horizontal Hank because he had been pinned down so many times by Japanese machine-gun fire while directing his platoon’s own machine-gun fire. After the Marauders were disbanded Henry served for a while with the Office of War Information (OWI), then was returned to the U.S. for medical care. In 1997 Staff Sergeant Henry Gosho was inducted into the U.S. Ranger Hall Of Fame.

7

A photograph taken in New York on September 12, 1945, which can be seen online on the University of California website, shows Henry Gosho with his wife and their eighteen-month-old daughter. According to the description of the photograph, “Sgt. Gosho was awarded a Presidential Unit Citation, Bronze Star, Pacific Ribbon with three campaign stars and Combat Infantryman’s Badge during 16 months service in the Burma-India theater with the Army Combat Intelligence of Merrill’s Marauders. A former resident of Seattle, Wash., he relocated to New York in August 1945 with his wife and baby daughter Carol Jeanne.” Henry Gosho started his career with the State Department in 1946 and entered the U.S. Foreign Service in 1954.”

Another photograph in the same collection, dated April 25, 1945, had the following description of Henry Gosho’s military service with the U.S. Army:

S/Sgt. Henry H. Gosho served 16 months in the Burma-India theatre attached to Army Combat Intelligence with General Frank Merrill’s Marauders until April, 1945, at which time he returned to the United States and is now convalescing at Fitzsimons General Hospital preparatory to being given a medical discharge. He volunteered for duty at Camp Savage in November, 1942, while living at the Minidoka Center, and volunteered for the Marauders in August, 1943. His was the first unit to be created from Camp Savage which left the United States in June, 1943. He wears the Presidential Citation, Bronze Star, the Pacific Ribbon with 3 campaign stars, the Combat Infantry Badge, and the shoulder patch of Merrill’s Marauders. General Merrill said to his Nisei outfit, I don’t know how we would get along without you boys. Sgt. Gosho was affectionately nicknamed Horizontal Hank because he hit the ground so much he wore it out. The doctors had declared him to be flat-footed and physically not qualified for combat. Despite these handicaps he wore out 4 pairs of shoes in walking 1030 miles and contracted malaria 7 times in addition to other tropical diseases. Prior to evacuation to Minidoka, his parents operated a drug store in Seattle. Photographer: Iwasaki, Hikaru Denver, Colorado.

An expanded biography of Henry Gosho appears in “Nisei in the U.S. Army Rangers Hall of Fame” online materials.

Staff Sergeant Henry Gosho

Staff Sergeant Henry Gosho was a member of the I &R Platoon, 3rd Bn, 5307th Composite Unit (Provisional), during World War II (the famous Merrill’s Marauders), and was inducted into the Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Benning, Georgia on June 19, 1997. Staff Sergeant Gosho repeatedly exposed himself to extreme danger by infiltrating the Japanese perimeter and listening to the Japanese officers giving their orders. He was able to return to his platoon and inform his commanding officer of what was going to happen, so they were well prepared for any attack. He was fired on so many times by machine guns that he was nicknamed “Horizontal Hank” for the number of times he had hit the ground.

Prior to his enlistment, Staff Sergeant Gosho and his family, including his pregnant wife, were forcibly relocated from their home in Seattle, Washington, to the Japanese Internment Camp in Idaho called Minidoka. Even under these circumstances, he volunteered to fight for his country.

The intelligence that he repeatedly received was largely responsible for the success of his unit. He was seriously wounded, lost a kidney, and suffered innumerable attacks of malaria, typhus, and jungle rot, and was medically discharged from the Army. Staff Sergeant Gosho is the recipient of the Bronze Star, Purple Heart, Presidential Unit Citation, Combat Infantryman’s Badge and numerous campaign ribbons.

After the war, he was the first Japanese American to be selected by the State Department and he served brilliantly for 17 years until retirement. In 1954, he entered the U.S. Foreign Service and was assigned to the Public Affairs Office at the American Embassy in Tokyo, Japan. In this position he was very instrumental in cementing relations between the United States and Japan during a crucial period in their diplomatic history.

Staff Sergeant Gosho passed away in 1992.

An interview conducted with Henry Gosho in 1989 by G. Lewis Schmidt for the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project shows that State Department Foreign Service officers and USIA information specialists worked closely with Voice of America broadcasters and in some cases were put in charge as managers of VOA foreign language services.

8The interview also shows that once democracy and private sector broadcasting were established in Japan, the need and demand by domestic stations for Voice of America programs quickly evaporated. This was also the case in Western Europe during the Cold War and in East-Central Europe after the Cold War.

GOSHO: All this is related to my getting into USIA, because I volunteered for combat duty in Burma with Merrill’s Marauders, at which time I met John Emmerson, a Foreign Service officer, who was assigned to General Stilwell’s headquarters as the political advisor. When John Emmerson left the area in 1944, he said to me, “If you’re ever in Washington, look me up, and maybe we can get you into the Foreign Service if you’re interested.”

I said, “Well, I’m interested,” even though I knew that at the time, the State Department did not employ Japanese-Americans.

1946: Post-War – Enters State Department 1960: Transfers to VOA

GOSHO: He said, “Well, maybe this war will change all that. But if you’re ever in Washington, look me up.” And I did. And he endorsed my application to the State Department.

I was assigned to the Japan desk of what was called the Foreign Activity Correlation Division, called FC. I was there from 1946 through the beginning of 1950. In those days, the Voice of America was under the State Department. In 1950, it was decided that they would start a Japanese language program, and they decided that I should be detailed to New York to help set up and oversee the Japanese program.

USIS Arranges to Broadcast World Series to Japan

Q: It seems to me that at one time USIS was arranging to broadcast World Series games. Tell me how that came about and what role you played in that.

GOSHO: (Laughs) That was before I was assigned at Tokyo. It occurred to me that even before the war, baseball was extremely popular in Japan. Probably, next to sumo, it was considered the national pastime. But because of that, I suggested to the Agency — well, at the time it was in State — I put in a proposal, which was approved, that we broadcast the World Series in Japanese to Japan. As it happened, I had gone to Japan earlier to recruit three NHK announcers, two of which happened to be sports announcers, so we were well prepared. I did the color commentary on it. Broadcasting a World Series was a great thrill to me, because I played baseball in high school in Japan, and it had always been my dream to see a World Series. Here I got the opportunity to do so.

One of the highlights of the World Series was when I conducted an interview with Casey Stengal, manager of the New York Yankees. I had asked him whether he foresaw a day when they would have a real World Series with the champion of America playing the champion of Japan. His response was, “You know, I went to Japan in 1934 with Babe Ruth, and now there was a great player.” He talked about Babe Ruth, and he said that Babe Ruth had gone to England. “Now, England, that’s a different situation. Baseball is not all that popular in Europe, but eventually there will be a day when baseball will become popular.” He switched from one topic to another so rapidly, in the blink of an eyelash, that I had a great deal of trouble interpreting what he said, Nonetheless, it went out over the air.

About two weeks later, we got several letters from Japan, saying, “We couldn’t understand a word of what that interpreter was saying.” Well, what the heck. I couldn’t understand a word of what Casey was trying to say either.

The significance, though, of that World Series was that we got reports from USIS Tokyo that there was an estimated audience of between 5 to 7 million who heard all seven games. That was one of the highlights of radio broadcasting, even in Japan, as the first broadcast in Japanese. Of course, today the Japanese are here not only broadcasting the World Series, but the Super Bowl, as well.

Original Description of the Photograph

Radio (Voice of America). New York. Standing in front of the champions “dugout” at the Yankee Stadium here, sportscasters of The Voice of America’s Japanese Unit pose with representatives of the New York Yankees World Series victors. Japanese baseball fans recently heard play-by-play commentaries in the Japanese language of the annual American sporting classic through the cooperation of the Voice of America and the Broadcasting Corporation of Japan. Voice of America broadcast on-the-spot accounts of all games by short-wave; the programs were subsequently re-broadcast by Broadcasting Corporation of Japan at a convenient hour for Japanese audiences. Left to right: Henry Gosho, editor for the Japanese Unit; Shiro Nose, former Broadcasting Corporation of Japan sports announcer who broadcast eye-witness commentary of the World Series for Voice of America; Eddie Lopat, New York Yankee “southpaw” pitcher; Minoru Okada, sportscaster who also covered the diamond battle for VOA; Casey Stengel, Yankee manager, and Bob Allison, sports editor for The Voice of America.

Photo measures 10 x 8.25inches. Photo is not dated and the photographer is unknown.

Notes:

- U.S. Information Agency, “The Voice of America” 1959 program schedule brochure. ↩

- Clifford Uyeda, “War Hero Henry Gosho Dies at 71,” Pacific Citizen, January 15, 1993, https://pacificcitizen.org/wp-content/uploads/archives-menu/Vol.116_%2302_Jan_15_1993.pdf. ↩

- Cold War Radio Museum, “OWI head Elmer Davis spread Soviet Katyn propaganda lie in World War II Voice of America broadcasts,” May 11, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/owi-head-elmer-davis-promotes-soviet-katyn-propaganda-lie-in-the-us-and-in-voice-of-america-radio-broadcasts/. ↩

- Cold War radio Museum, “Stalin Peace Prize Voice of America Editor Duped by Soviet Propaganda,” January 29, 2020, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalin-peace-prize-voice-of-america-editor-duped-by-soviet-propaganda/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “How the Roosevelt Administration Shipped Polish Refugee Orphans to Mexico In Locked Trains and Lied About It to Protect Stalin: The Untold Story of Polish Refugee Children from Soviet Russia: “A Group Lost in History,” Cold War Radio Museum, December 9, 2018, https://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/how-u.s.-shipped-polish-refugee-orphans-from-russia-to-mexico-in-locked-trains-and-lied-about-it-to-protect-stalin/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Zofia Korbonska — LIPIEN: Remembering A Polish American Patriot,” The Washington Times, September 1, 2010, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2010/sep/1/remembering-a-polish-american-patriot/. ↩

- Marauder.org, “Henry Gosho (Horizontal Hank), http://www.marauder.org/gosho.htm. ↩

- Schmidt, G. Lewis, and Henry Gosho. Interview with Henry Gosho. January 4, 1989. Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib000436/. ↩

Add Comment