Rep. Howard H. Buffett, father of American investor Warren Buffett, was concerned in 1947 about domestic propaganda activities by the Voice of America.

As the U.S. Congress was debating in June 1947 the eventual passage of the Smith-Mundt Act, which implicitly placed restrictions on domestic dissemination of government news through the Voice of America (VOA) while funding expansion of State Department’s cultural and academic exchange programs, Congressman Howard Buffett (R-NE) expressed concerns that officials in charge of VOA may have been secretly planning domestic propaganda activities. As it turned out, State Department officials had no plans to distribute U.S. government radio broadcasts domestically because such a move would kill the funding not only for VOA but also for the public diplomacy programs the State Department cared about most of all. Congressman Buffett was right, however, that U.S. diplomats were using VOA to influence U.S. public opinion to drum up support for their information outreach budget.

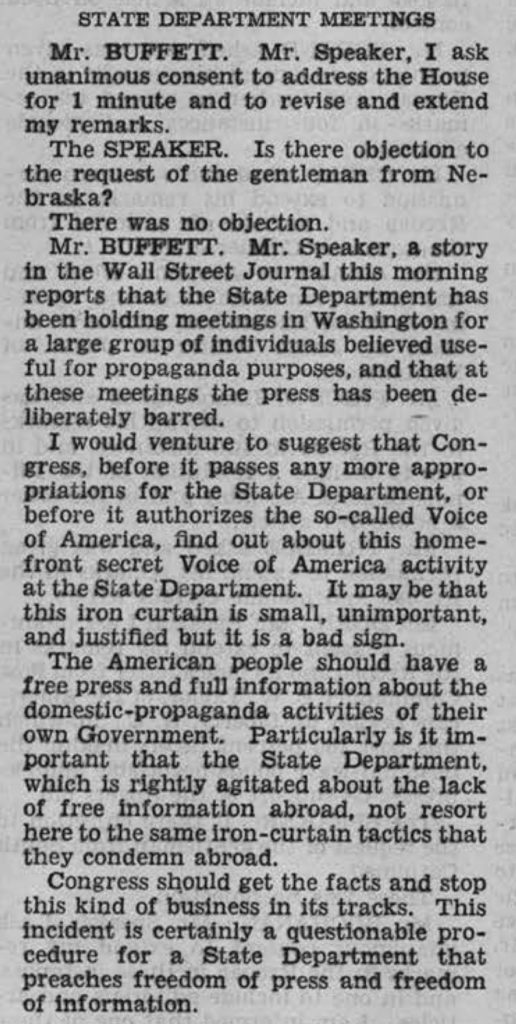

When Rep. Buffett told the House of Representatives that “the American people should have a free press and full information about the domestic-propaganda activities of their own Government, he was objecting to closed meetings, to which the State Department invited propaganda experts and representatives of private organizations. U.S. media outlets were deliberately barred from covering the meetings. He told the House on June 9, 1947, a few days after members debated some of the provisions of the future Smith-Mundt Act, that Congress should investigate such “home-front secret Voice of America activity” before it passes any more appropriations. He was expressing longlasting congressional concern over possible misuse of VOA by the Executive Branch to propagandize to Americans. 1

“I would venture to suggest that Congress, before it passes any more appropriations for the State Department, or before it authorizes the so-called Voice of America, find out about this home-front secret Voice of America activity at the State Department. It may be that this iron curtain is small, unimportant, and justified but it is a bad sign.” 2

By limiting U.S. government’s public diplomacy and broadcasting activities only to foreign countries, the Smith-Mundt Act when it was eventually passed by Congress and signed by President Truman in 1948 effectively prevented direct distribution of Voice of America news in the United States while allowing U.S. media and members of Congress research access to evaluate VOA programs. A ban on domestic distribution was not explicitly included in the law, but lawmakers made sure that VOA broadcasts would only be directed abroad and, on top of that, would not compete with U.S. domestic media either abroad or in the United States. An explicit ban on domestic distribution of Voice of America broadcasts was added later, but it was commonly understood since 1948 that VOA would have no domestic media role of any kind.

In debating the Smith-Mundt Act in 1947, members of Congress were generally supportive of expanding Voice of America foreign broadcasting and State Department public diplomacy and academic exchange programs as necessary to counter the growing threat of Soviet influence. Many, however, were also mindful of earlier pro-Soviet domestic U.S. government propaganda by the Roosevelt administration through the wartime Office of War Information (OWI), where VOA radio broadcasts were first launched in 1942 under various early names before it became known as the Voice of America. OWI’s domestic and foreign propaganda was essentially the same, coordinated by the same top officials, and repeated many of the same Soviet false claims and lies, deceiving both Americans and audiences abroad.

John Houseman, the man who was later known as the first VOA director, was denied a U.S. passport by the State Department in 1943 because he was suspected of pro-Soviet sympathies and of hiring Communists. 3 One of the first chief writers of VOA news was Howard Fast, a future Communist Party USA member and the 1953 winner of the Stalin Peace Prize worth approximately $235,000 in today’s dollars. 4

As the Second World War continued, more and more members of Congress of both parties became convinced that OWI and VOA staff had been infiltrated by Soviet and communist sympathizers. There were many warnings in Congress that OWI information programs in the United States and VOA broadcasts abroad reflected Soviet propaganda. In 1943, U.S. lawmakers nearly defunded OWI over such concerns in the middle of the war with two deadly enemies. That is how unpopular domestic U.S. government propaganda was perceived at the time. Ultimately, Congress allowed OWI overseas radio broadcasts to continue but greatly reduced funding for its domestic information activities. From time to time, members of Congress would expose foreign Communists working on Voice of America programs. Some of these early VOA broadcasters later ended up working for Communist regimes behind the Iron Curtain. 5

While many journalists managers and other staffers did not transfer from OWI to the State Department in 1945, some of the early OWI pro-Soviet fellow travelers were still working at VOA in 1947. It was still before such outstanding anti-communist journalists as the Polish anti-Nazi fighter Zofia Korbońska were hired upon the recommendation of a strong critic of VOA radio broadcasts overseen by the State Department, former Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane. The contributions of journalism who had a first hand experience with Communism did not make a significant difference until about 1952. Disappointed with a slow pace of reform at the State Department and VOA, Ambassador Lane and other prominent Americans turned their attention to creating Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberation (later renamed Radio Liberty) in the early 1950s.

Some of the concerns over Soviet propaganda influence within the U.S. information agency were later addressed in the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act. The legislation required a much higher level of security clearances for VOA personnel in addition to making it clear, although not in the most direct way, that Voice of America programs would only be distributed outside of the United States.

Congress would not have approved funding for VOA in 1948 if its programs were to be broadcast domestically. This was due to both fears of domestic propaganda tainted with Soviet influence as well as a desire to prevent any government competition with private media in the United States. Domestic broadcasting by VOA was not even seriously contemplated as it would have been a non-starter. As long as VOA was within the State Department, its academic exchange programs and other public diplomacy activities would also not get any funding if there were even a suspicion of domestic propaganda activity by VOA or any sign of domestic partisanship. The Voice of America was saved from many potential scandals when the foreign target area designation was put in the Smith-Mundt Act, but as late as 1952, the VOA was still being criticized for being timid and less then fully effective against Soviet propaganda. A bipartisan congressional committee also strongly condemned World War II OWI propaganda activities, both domestic and foreign. 6

In later years of the Cold War there was a push from officials in charge of VOA to get Congress to eliminate restrictions on domestic program content distribution. During the Obama administration, the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act and subsequent legislation were modified and original restrictions weakened but not completely eliminated. The Smith-Mundt Modernization Act of 2012, which was contained within the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 (section 1078 (a)), amended the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (Smith-Mundt Act) and the Foreign Relations Authorization Act of 1987, allowing for materials produced by the State Department and the Broadcasting Board of Governors (BBG) to be made available to anybody on request within the United States. The Voice of America is still prohibited from targeting Americans with its programs, but they can be easily seen by Americans on the web, including social media. In 2018, VOA was caught illegally targeting Americans with Facebook ads and has been accused of engaging in partisan propaganda since at least the 2016 presidential election campaign.

In 1947, U.S. Rep. Howard Homan Buffett (1903 – 1964), who was an American businessman, investor, and politician, was expressing commonly shared fears that the Executive Branch of the U.S. federal government could employ the Voice of America or even the State Department to promote a particular administration’s policies to Americans using misleading propaganda. Howard H. Buffett was a four-term Republican congressman from Nebraska and the father of the American billionaire investor. Warren Buffett.

Congressional Record – House

House of Representatives

Monday, June 9, 1947

STATE DEPARTMENT MEETINGS

Mr. BUFFETT. Mr. Speaker, I ask unanimous consent to address the House for 1 minute and to revise and extend my remarks.

The SPEAKER. Is there objection to the request of the gentleman from Nebraska?

There was no objection.

Mr. BUFFETT. Mr. Speaker, a story in the Wall Street Journal this morning reports that the State Department has been holding meetings in Washington for a large group of individuals believed useful for propaganda purposes, and that at these meetings the press has been deliberately barred.

I would venture to suggest that Congress, before it passes any more appropriations for the State Department, or before it authorizes the so-called Voice of America, find out about this home-front secret Voice of America activity at the State Department. It may be that this iron curtain is small, unimportant, and justified but it is a bad sign.

The American people should have a free press and full information about the domestic-propaganda activities of their own Government. Particularly is it important that the State Department, which is rightly agitated about the lack of free information abroad, not resort here to the same iron-curtain tactics that they condemn abroad.

Congress should get the facts and stop this kind of business in its tracks. This incident is certainly a questionable procedure for a State Department that preaches freedom of press and freedom of information.

7

During an earlier debate on the floor of the House of Representatives, Rep. Buffett said on January 23, 1947 that Communism represents and has always used “the forces of hatred.” 8 But despite being a critic of Communism and Soviet Russia, Buffett was also an anti-interventionist and a critic of ineffective government programs and wasteful spending. He strongly opposed many of the Truman Plan foreign aid provisions for helping countries such as Greece and Turkey to resist the perceived threat of a communist uprising and Soviet domination. He believed these threats to be exaggerated in countries like Turkey and Greece or in Western Europe.

On June 16, 1947, he inserted in the Congressional Record the Wall Street Journal article about what he feared were secret meetings at the State Department designed to influence U.S. public opinion to support a more interventionist foreign policy. He was also concerned that journalists were barred from covering these meetings .

The Wall Street Journal article from June 9 appeared in the Congressional Record under the title, “Is the State Department, Like the Communists, Allergic to Free News Coverage?” 9

Congressional Record – House

House of Representatives

Monday, June 16, 1947

Is the State Department, Like the Communists, Allergic to Free News Coverage?

EXTENSION OF REMARKS

of

HON. HOWARD H. BUFFETT OF NEBRASKA

IN THE HOUSE OP REPRESENTATIVES

Monday, June 16, 1947

Mr. BUFFETT. Mr. Speaker, not long ago the Communists alibied their opposition to free news coverage with the claim that American news reporting was biased and distorted. Recent actions of the State Department might indicate that they hold views not unlike the Russians in this respect.

The Kiplinger Washington Letter of June 14 reveals some information about secret seminars being held by the State Department from which all news reporters are carefully excluded.

However, the most complete expose of this secret indoctrination was carried in the Wall Street Journal of June 9, as follows:

PIN A BADGE, TAKE A VOW OF SILENCE—LEARN OUR FOREIGN POLICY—TO SPREAD “INFORMATION.” STATE DEPARTMENT SHUTS OUT PRESS, TALKS TO CLUB, CHURCH FOLK

(By Vermont Royster)WASHINGTON.—The State Department is unlimbering its biggest propaganda guns in support of its foreign policy.

The diplomats are holding a series of “off the record,” unpublicized conferences In Washington and elsewhere about the country, with representatives of women’s clubs, church groups, fraternal organizations, and Independent voters’ leagues. In these sessions, top officials of the State Department have set out to sell the Truman “Stop Russia” Doctrine and gather aid for other phases of the administration’s foreign program. 10

Despite warnings from Rep. Buffett and others, many members of Congress of both parties were generally supportive in 1947 of funding Voice of America overseas broadcasts and the State Department’s public diplomacy activities provided they were directed toward changing public opinion and countering Soviet propaganda abroad. As long as Americans were not being targeted by propaganda produced by possibly pro-Soviet officials and broadcasters, Congress was willing to provide more money for VOA and the State Department if sufficient safeguards were in place. Educating Americans about the Soviet threat was seen, at least by some lawmakers, as a possibly desirable activity for the U.S. government but not through any domestic Voice of America broadcasting. Even with promises of better security clearance procedures, many members of Congress, particularly Republicans, were still suspicious of foreign broadcasters working for the Voice of America and doubted the competence of some of left-leaning State Department supervisors of VOA journalists.

At the same time, other members of Congress, even including some Republicans, were not terribly concerned about closed State Department meetings or its efforts to educate Americans about foreign policy undertaken by U.S. diplomats. One of the supportive lawmakers was a Republican congresswoman from Ohio, Francis P. Bolton, but even she expressed concern that the State Department briefings were not open to all members of Congress. She made her remarks on June 9, 1947. 11

Congressional Record – House

House of Representatives

Monday, June 9, 1947

STATE DEPARTMENT MEETINGS

Mrs. BOLTON. Mr. Speaker. I ask unanimous consent to address the House for 1 minute.

The SPEAKER. Is there objection to the request of the gentlewoman from Ohio?

There was no objection.

Mrs. BOLTON. Mr. Speaker, it was my pleasure to take part in this “secret meeting” of the State Department last week. I should like to inform the Congress that to my mind that meeting of some 250 delegates from some 250 organizations of this country, which was pursuant to legislation parsed by this House to give information on foreign policy to the people of the country, was one of the most progressive, sane, and constructive conferences I have ever attended. Mr. PETE JARMAN, Senator CONNALLY, Senator FLANDERS, and I spoke on the evening when these delegates were given the opportunity to speak to and with the Congress.

In order to have the very freest discussion possible—so that the hair could be taken down—these meetings were “off the record.”

On the evening when we four Members of Congress participated I can assure you the hair was taken down very constructively.

I agree that it would have been advisable had the State Department opened the meetings to Members of the Congress, but I want to say to this body. Mr. Speaker, that I feel this effort on the part of the Department to give information to one of the great sections of our citizenship—members of 250 national organizations—to have been a most com- mendable one. It is my earnest hope and my expectation that the material given these delegates will be made available promptly to the Congress. 12

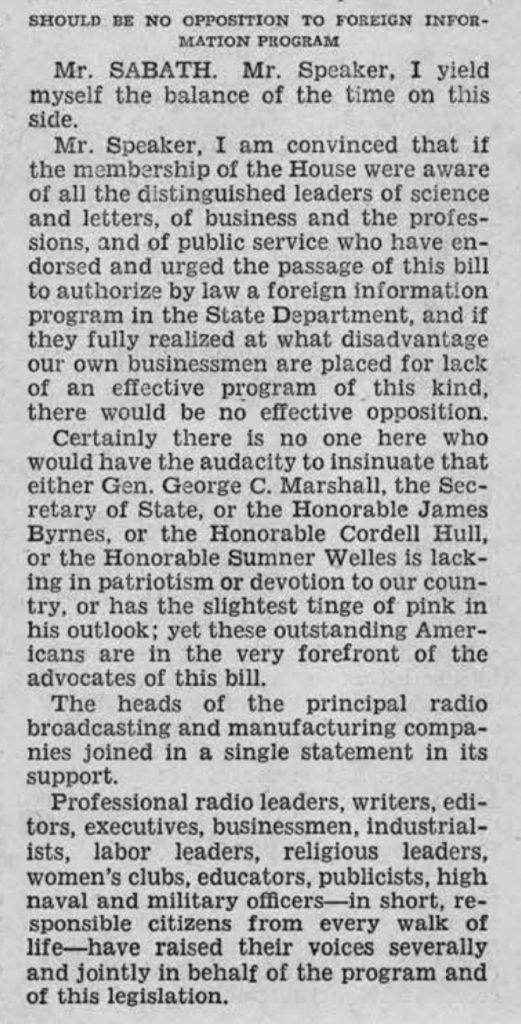

One of many congressional backers of the eventual Smith-Mundt bill was Rep. Adolph J. Sabath (D-IL). In a House floor speech on June 6, 1947, the Czech-American politician from Chicago listed a number of prominent Americans who were supportive of the State Department’s information programs, including the Voice of America. He mentioned General Dwight D. Eisenhower and Secretary of State General George C. Marshall, but he did not indicate in any way that they were in favor of VOA programs to be distributed domestically.

Back in 1944, Congressman Sabath had made a prediction that Josef Stalin would honor his promises of respecting democracy and freedom in Eastern Europe. “I have had every reason to believe the statements made by Marshal Stalin and other official representatives of Russia that none of the smaller countries would be deprived of their rights, lands, freedom, and liberty,” Rep. Sabath told the House of Representatives on March 23, 1944. 13 While this Soviet propaganda message was also repeated constantly in Voice of America radio broadcasts during the war, not all members of the U.S. Congress, and not even all members of the Roosevelt administration, were fooled by such assurances, although they became the basis of President Roosevelt’s Russia policy.

One of the American diplomats mentioned by Rep. Sabath in 1947 was former Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles. It was he who in 1943 warned the Roosevelt White House in a secret memo that Voice of America Director John Houseman was a Soviet sympathizers who hired Communists to work on VOA broadcasts. 14 Welles was one of President Roosevelt’s closest liberal friends and a foreign policy advisor. Welles endorsed the State Department’s decision to deny Houseman a U.S. passport he requested for official travel abroad, which in turn led to Houseman’s resignation a few months later from his radio job at the Office of War Information. 15

It was obvious to almost anyone following congressional debates since 1942 that if Voice of America programs were to be distributed in the United States after the war and/or compete with U.S. domestic media, it would kill any funding for VOA, as well as for the State Department’s cultural and educational exchanges abroad or at home.

General Eisenhower, while being supportive of countering Soviet propaganda, had a very low opinion of the Office of War Information and the Voice of America even if at other times he praised some of OWI’s psychological warfare activities during World War II. In his post-White House book Waging Peace published in 1965, he accused the pro-Soviet OWI VOA broadcasters of “insubordination” toward President Roosevelt and disclosed that a Voice of America journalist tried to derail his Middle East policy by attempting to manufacture fake domestic political news.

“In Washington I had been told that a representative of the Voice of America (our governmental radio overseas) had tried to obtain from a senator a statement opposing our landing of troops in Lebanon. In a state of some pique I informed Secretary Dulles that this was carrying the policy of ‘free broadcasting’ too far. The Voice of America should, I said, employ truth as a weapon in support of Free World, but it had no mandate or license to seek evidence of lack of domestic support of America’s foreign policies and actions.” 16

Before being elected as U.S. President in 1952, General Eisenhower devoted his private efforts toward the creation of Radio Free Europe.

In 1947 concerns about domestic VOA propaganda were still quite real after the OWI experiment, but many members of Congress and other influential Americans also saw the need to strengthen the U.S. response to Soviet propaganda and indoctrination through overseas information programs. 17

Congressional Record – House

House of Representatives

Monday, June 6, 1947

SHOULD BE NO OPPOSITION TO FOREIGN INFORMATION PROGRAM

Mr. SABATH. Mr. Speaker, I yield myself the balance of the time on this side.

Mr. Speaker, I am convinced that if the membership of the House were aware of all the distinguished leaders of science and letters, of business and the profes- sions, and of public service who have en- dorsed and urged the passage of this bill to authorize by law a foreign information program in the State Department, and if they fully realized at what disadvantage our own businessmen are placed for lack of an effective program of this kind, there would be no effective opposition.

Certainly there is no one here who would have the audacity to insinuate that either Gen. George C. Marshall, the Secretary of State, or the Honorable James Byrnes, or the Honorable Cordell Hull, or the Honorable Sumner Welles is lacking in patriotism or devotion to our country, or has the slightest tinge of pink in his outlook; yet these outstanding Americans are in the very forefront of the advocates of this bill.

The heads of the principal radio broadcasting and manufacturing companies joined in a single statement in its support.

Professional radio leaders, writers, editors, executives, businessmen. Industrial- ists, labor leaders, religious leaders, women’s clubs, educators, publicists, high naval and military officers—in short, responsible citizens from every walk of life—have raised their voices severally and jointly in behalf of the program and of this legislation. 18

At the same time, critics and even some of the supporters of VOA foreign broadcasts abroad were expressing strong doubts about their effectiveness and concerns over possible Soviet influence among VOA staff. Rep. John Edgar Chenoweth (R-CO) told the House on June 6, 1947 that he had a committee investigator check on the VOA foreign broadcasting operations at the New York office and became convinced that “this program is too extravagant and could be carried on with much greater efficiency and economy.” In a comment hinting the future creation of Radio Free Europe and Radio Liberty under the secret oversight by the CIA and secret appropriations from the U.S. Congress, Rep. Chenoweth also said that “if it is wise and necessary for the United States to enter the propaganda field then that agency should be established in some other department of our Government.” There was a lot of confusion in Congress and among Americans in general what is and what is not propaganda. Many wrongly assumed that countering Soviet disinformation in itself amounted to propaganda. There were also fears that communist and Soviet sympathizers were still employed by the Voice of America and the State Department.

One of the chief authors of the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act, Rep. Karl E. Mundt (R-MI), attempted to allay such concerns by stressing that “those who worry as all of us rightfully should lest un-American influences creep into this or any other division of the State Department,” should be assured that “all people employed or assigned to duties under this act must first be screened and certified as to loyalty and security by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.” Rep. Mundt also pointed out that “to make positive that this becomes truly the voice of America we stipulate that the employment of aliens shall be sharply limited to services related to the translation or

narration of colloquial speech in foreign languages when suitably qualified United States citizens are not available.” In addressing another concern, Rep. Mundt stressed that “this program will not establish competitive Government radio and press agencies to compete with private American enterprise.” 19

We have provided over 20 safeguards in the Mundt bill, not only against infiltration of un-American individuals into the organization which is to be created, but safeguards protecting the economy of America; safeguards providing that Congress be kept informed of what is going on; safeguards providing for guidance and counsel and advice from the private professions and industry to help the State Department develop the best possible type of program; safeguards precluding the employment of aliens except in those areas where Americans are unable to speak the dialect being broadcast; safeguards so that the Voice of America will be spoken by Americans and the spirit of America will be interpreted by loyal American citizens who are enthusiastic, sincere, and able exponents and disciples of our cherished ways of life.

We have included safeguards providing that wherever possible the State Department must use private agencies in order to carry out the program; safe- guards so that Congress by concurrent resolution can stop the program or any portion of it any time it chooses without a Presidential signature, because we want the Congress and the country to feel secure and convinced that this is a pro- gram of Americans broadcasting the voice of America in a manner in which all Americans can be proud.

Rep. Mundt was, however, willing to admit that the Voice of America needed reforms. Other members of Congress demanded that management and programming reforms should come first before more money is given to VOA.

During the debate in the House of Representatives on June 13, 1947, Rep. John Taber (R-NY) said that the Voice of America’s very first broadcast to Russia earlier that year was a “totalitarian philosophy broadcast.” He added, however, that “if it was a bill providing for the Voice of America, and it was honestly to be the Voice of America, I would support it.” 20

U.S. lawmakers were more than willing to fund VOA broadcasting activities abroad if they would be free of foreign influence and effective against Soviet propaganda. State Department officials knew this and used this opportunity to get money also for academic exchange programs and other public diplomacy activities. Everybody also knew that there were limits on what members of Congress would tolerate in U.S. government information outreach. Mindful of the past abuses under the Office of War Information, they would not support the Voice of America even abroad if there were any chance that VOA broadcasts could be used for spreading partisan propaganda in the United States. Rep. Taber’s speech represented a warning that U.S. taxpayers’ money should not be used by federal government officials to lobby Americans for money and support for their favorite programs and policies.

Congressional Record – House

House of Representatives

Monday, June 13, 1947

Mr. TABER. Mr. Chairman, I rise in opposition to the pro forma amendment. Mr. Chairman, I cannot support this bill at this point. If it was a bill providing for the Voice of America, and it was honestly to be the Voice of America, I would support it. They have not yet cleaned up that situation in the State Department, which has cried aloud for attention ever since the whole thing started. Their very first broadcast to Russia was a totalitarian philosophy broadcast. I have had in my hands, and I have in my office. 500 broadcasts, and out of the whole 500 I defy any man to find one that would do America a bit of good, and he would find many that would do a lot of harm. The management of the thing has been bad. For a year and a half, Mr. Benton has been in charge of it, and he has not cleaned it up. There is still Haldore Hansen in charge of this cultural relations subject, the same fellow under whose management all those paintings and that sort of thing were bought. There is William T. Stone, and Charles A. Thompson, in charge of the broadcasts. Neither one of them should be on any pay roll of the Government of the United States.

Mr. Stone put out a circular on the 1st day of May after the Appropriations Committee had operated on this activity because it was not the Voice of America. I have it here, and shall insert it in the RECORD. It is a circular in clear violation of the anti lobbying law. I wonder if we are going to have that sort of thing going on.

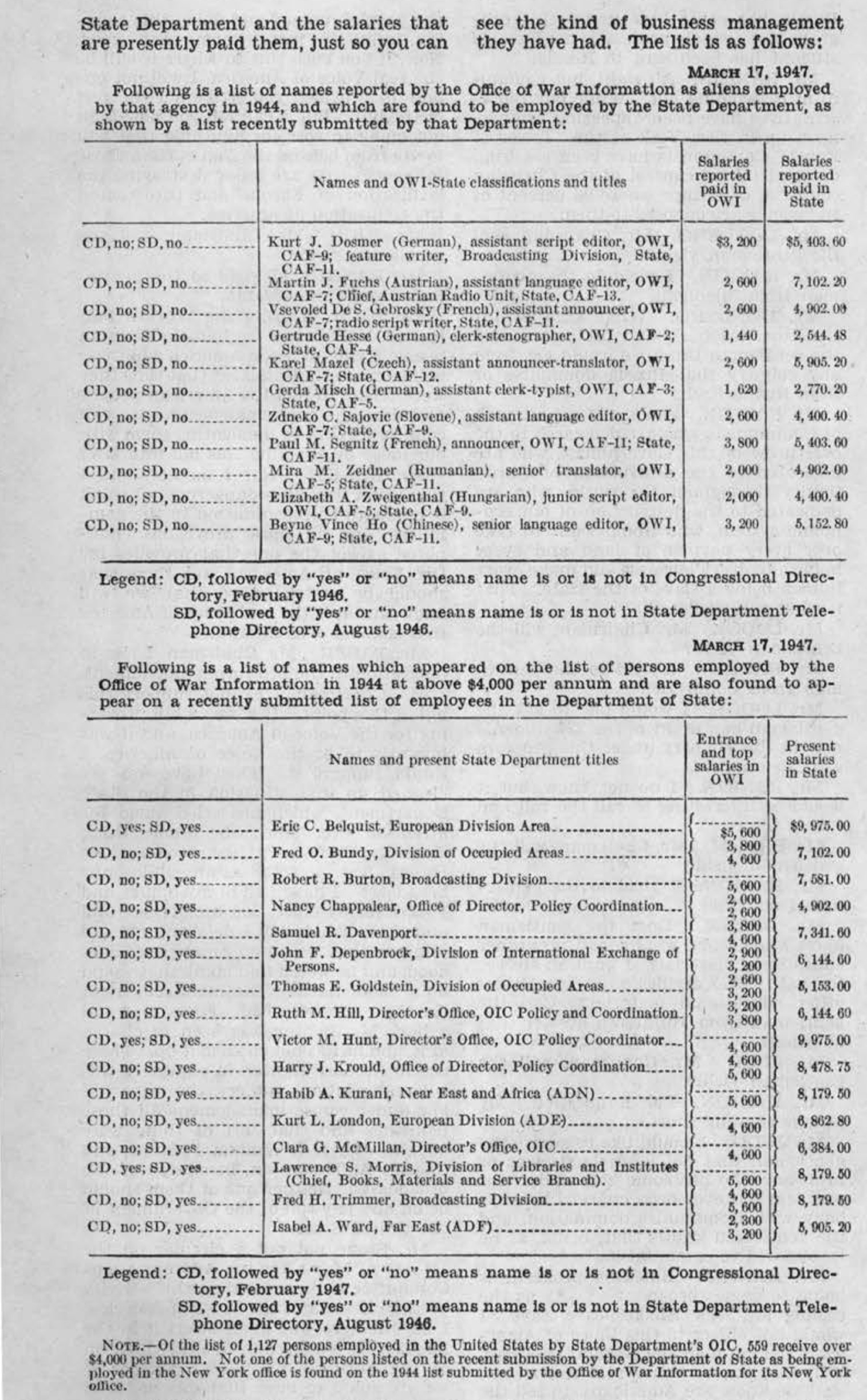

I also call your attention to the way they have done business. I have before me a comparison of the salaries that were paid a group of these people at the time they came from the OWI to the State Department and the salaries that are presently paid them, just so you can see the kind of business management they have had. The list is a follows: 21

Rep. Taber was right to question first VOA broadcasts in Russian launched in 1947. Before that, VOA did not broadcast in Russian because pro-Soviet officials in the Office of War Information did not want to offend Stalin. One of the early contributors to OWI information programs and later a volunteer in launching first VOA broadcasts in Russian in 1947 was journalist Kathleen Harriman, daughter of President Roosevelt’s wartime ambassador to Moscow W. Averell Harriman. She had worked for OWI as a young reporter in London and later in Moscow, where she accompanied her father. It was Ambassador Harriman who in 1944 sent his 25-year-old daughter on a Soviet-organized propaganda trip to the Katyn Forest near Smolensk, the site of the mass murder of thousands of Polish military officers and members of the Polish intelligentsia. After her trip to Katyn, she produced a report for the State Department which supported the Soviet propaganda claim that the Germans were the perpetrators of the mass murder. The Polish prisoners of war in Soviet hands were in fact executed in the spring of 1940 by the NKVD secret police on the orders of Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Politburo. As Russia was then America’s military ally fighting Nazi Germany, President Roosevelt did not want to disclose Stalin’s genocidal crimes to Americans and foreign audiences. For several years the Voice of America helped to spread one of the greatest Soviet propaganda lies of the 20th century. American diplomat, Charles Thayer, who was in charge of launching the first VOA Russian broadcast and who hired Kathleen Harriman as a volunteer, did not believe that Stalin was responsible for the Katyn massacre. He was later VOA Director before being pushed out of the Foreign Service over a number of unconfirmed scandals of personal nature.

The primary purpose of the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948, commonly known as the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act, was to fund State Department’s cultural and educational exchanges and other public diplomacy activities, but the price of the bill’s passage was the implicit ban on domestic propaganda activities and a much improved system of security clearances for Voice of America broadcasters working in the U.S. State Department.

U.S. lawmakers did not want any more Soviet sympathizers and Communists such as Howard Fast to be in charge of the Voice of America and writing VOA news. The Smith-Mundt Act of 1948, however, did not prohibit access to U.S. government news by American media. It only placed strict restrictions on how it could be done. Just in case, Congress clearly stated in Title V SEC. 501 and SEC. 502 of the 1948 law that VOA programming would be directed only toward foreign audiences and that such U.S.-funded broadcasts should not compete with private media.

U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (Public Law 80-402) – Smith-Mundt Act

TITLE V-DISSEMINATING INFORMATION ABOUT THE UNITED STATES ABROAD

GENERAL AUTHORIZATION

SEC. 501. The Secretary is authorized, when he finds it appropriate, to provide for the preparation, and dissemination abroad, of information about the United States, its people, and its policies, through press, publications, radio, motion pictures, and other information media, and through information centers and instructors abroad. Any such press release or radio script, on request, shall be available in the English language at the Department of State, at all reasonable times following its release as information abroad, for examination by representatives of United States press associations, newspapers, magazines, radio systems, and stations, and, on request, shall be made available to Members of Congress.

POLICIES GOVERNING INFORMATION ACTIVITIES

SEC. 502. In authorizing international information activities under this Act, it is the sense of the Congress (1) that the Secretary shall reduce such Government information activities whenever corresponding private information dissemination is found to be adequate ; (2) that nothing in this Act shall be construed to give the Department a monopoly in the production or sponsorship on the air of short-wave broadcasting programs, or a monopoly in any other medium of information.

It was always legal for Americans and American media to use U.S. government-funded news programs in the United States and rebroadcast such programs if they had obtained access to them on their own.

In other words, there were no legal prohibitions on using such programs by American citizens, residents of the United States or American media outlets rebroadcasting such programs in the United States. They would have to find and record these programs themselves without any help from government officials. Once these programs were put on the Internet, it was relatively easy. In fact, Americans newspapers and radio stations were using Voice of America programs under the 1948 law without any major problems. Domestic demand for such programs was, however, quite low.

Prohibitions in the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948 applied only to the government. Under the old law, State Department, United States Information Agency, and later Broadcasting Board of Governors officials were prohibited from disseminating such material in the United States.

To get the 1948 law changed, U.S. government officials released misleading information that it was somehow illegal or impossible for Americans to use these programs. In fact, these programs had been available earlier through shortwave radio transmissions and later most of them, including audio and video, were available and downloadable for reuse and rebroadcast off the Internet.

In some cases, broadcasters would have had problems getting broadcast quality video or video tapes, although they would have been able to download such programs off satellites unless the signal was scrambled. There was no big demand domestically for these programs and those who wanted them were able to find them on the Internet.

Under the old law, government officials were not allowed to assist in releasing these programs or in making them available for immediate use. They were also not allowed to market these programs in the United States.

As an additional check on the State Department and the Voice of America, TITTLE VI of the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act provided for the creation of two bipartisan advisory commissions.

U.S. Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (Public Law 80-402) – Smith-Mundt Act

TITLE VI-ADVISORY COMMISSIONS TO FORMULATE POLICIES

SEC. 601. There are hereby created two advisory commissions, (1) United States Advisory Commission on Information (hereinafter in this title referred to as the Commission on Information) and (2) United States Advisory Commission on Educational Exchange (here- inafter in this title referred to as the Commission on Educational Exchange) to be constituted as provided in section 602 . The Com-missions shall formulate and recommend to the Secretary policies and programs for the carrying out of this Act…

Title X provided for strict loyalty checks on Voice of America and State Department personnel which amounted to much better background investigations of potential employees for security clearance purposes.

TITLE X-MISCELLANEOUS

LOYALTY CHECK ON PERSONNEL

SEC. 1001. No citizen or resident of the United States, whether or not now in the employ of the Government, may be employed or assigned to duties by the Government under this Act until such individual has been investigated by the Federal Bureau of Investigation and a report thereon has been made to the Secretary of State: Provided, however, That any present employee of the Government, pending the report as to such employee by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, may be em- ployed or assigned to duties under this Act for the period of six months from the date of its enactment. This section shall not apply in the case of any officer appointed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate.

1985 Amendment from Senator Edward Zorinsky (D-NE) to the Smith-Mundt Act of 1948

In 1985, Senator Edward Zorinsky (D-NE), introduced an amendment to the 1948 Smith-Mundt Act which made prohibition on domestic propaganda by the Voice of America even more explicit.

Congressional Record of the 99th Congress, 1st Session, June 7, 1985 (legislative day of June 3, 1985):

Mr. ZORINSKY. Mr. President, I ask unanimous consent that further reading of the amendment be dispensed with.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. Without objection, it is so ordered.

The amendment is as follows:

On page 19, after line 9 add the following new section:

SEC. 206. BAN ON DOMESTIC ACTIVITIES BY THE USIA.

No funds authorized to be appropriated to the United States Information Agency shall be used to influence public opinion in the United States. No program material prepared by the United States Information Agency shall be distributed within the United States. This section shall not apply to programs carried out pursuant to the Mutual Educational and Cultural Exchange Act of 1961, as amended (Public Law 87-256).

Mr. ZORINSKY. Mr. President, I offer this amendment to prohibit USIA from engaging in domestic propaganda and to restate the existing prohibitions on domestic dissemination of USIA products.

By law, the USIA cannot engage in domestic propaganda. This distinguishes us, as a free society, from the Soviet Union where domestic propaganda is a principal government activity.

There is considerable discussion within USIA about using the Agency’s so-called second mandate to engage in domestic propaganda. The second mandate — “telling America about the world” — has never been implemented. It should not now be implemented as part of a USIA strategy to propagandize the American people on foreign policy issues.

The American taxpayer certainly does not need or want his tax dollars used to support U.S. Government propaganda directed at him or her. My amendment ensures that this will not occur.

Mr. President, I have checked with the majority floor manager and the minority floor manager and they have indicated this may be acceptable to them.

Mr. LUGAR. Mr. President, the amendment of the distinguished Senator from Nebraska essentially restates law with regard to the USIA. The Senator feels that it is important that this law be not only restated but perhaps reenforced by the emphasis of this amendment. We accept the amendment and commend it to the Senate.

The PRESIDING OFFICER. Is there further debate? If not, the question is on agreeing to the amendment.

The amendment (No. 296) was agreed to.

Mr. ZORINSKY. Mr. President, I move to reconsider the vote by which the amendment was agreed to.

Mr. LUGAR. I move to lay that motion on the table.

The motion to lay on the table was agreed to.

Section 1078 of National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2013 (Public Law 112-239)

Section 1078 of National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2013 (Public Law 112-239) lifted the restriction on the Voice of America providing its programs upon request to domestic U.S. media, but the modified Smith-Mundt Act specifically retained the prohibition on VOA targeting Americans with its media programs which the U.S. Congress still specifically wants to be only directed abroad.

‘GENERAL AUTHORIZATION

‘Sec. 501. (a) The Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors are authorized to use funds appropriated or otherwise made available for public diplomacy information programs to provide for the preparation, dissemination, and use of information intended for foreign audiences abroad about the United States, its people, and its policies, through press, publications, radio, motion pictures, the Internet, and other information media, including social media, and through information centers, instructors, and other direct or indirect means of communication.

‘(b)(1) Except as provided in paragraph (2), the Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors may, upon request and reimbursement of the reasonable costs incurred in fulfilling such a request, make available, in the United States, motion pictures, films, video, audio, and other materials disseminated abroad pursuant to this Act, the United States International Broadcasting Act of 1994 (22 U.S.C. 6201 et seq.), the Radio Broadcasting to Cuba Act (22 U.S.C. 1465 et seq.), or the Television Broadcasting to Cuba Act (22 U.S.C. 1465aa et seq.). Any reimbursement pursuant to this paragraph shall be credited to the applicable appropriation account of the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors, as appropriate. The Secretary and the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall issue necessary regulations–

‘SEC. 208. CLARIFICATION ON DOMESTIC DISTRIBUTION OF PROGRAM MATERIAL.

‘(a) In General- No funds authorized to be appropriated to the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors shall be used to influence public opinion in the United States. This section shall apply only to programs carried out pursuant to the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (22 U.S.C. 1431 et seq.), the United States International Broadcasting Act of 1994 (22 U.S.C. 6201 et seq.), the Radio Broadcasting to Cuba Act (22 U.S.C. 1465 et seq.), and the Television Broadcasting to Cuba Act (22 U.S.C. 1465aa et seq.). This section shall not prohibit or delay the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from providing information about its operations, policies, programs, or program material, or making such available, to the media, public, or Congress, in accordance with other applicable law.

‘(b) Rule of Construction- Nothing in this section shall be construed to prohibit the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors from engaging in any medium or form of communication, either directly or indirectly, because a United States domestic audience is or may be thereby exposed to program material, or based on a presumption of such exposure. Such material may be made available within the United States and disseminated, when appropriate, pursuant to sections 502 and 1005 of the United States Information and Educational Exchange Act of 1948 (22 U.S.C. 1462 and 1437), except that nothing in this section may be construed to authorize the Department of State or the Broadcasting Board of Governors to disseminate within the United States any program material prepared for dissemination abroad on or before the effective date of section 1078 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013.

SUPPORT THE WORK OF COLD WAR RADIO MUSEUM

IF YOU APPRECIATE SEEING THESE ARTICLES AND COLD WAR RADIO MEMORABILIA

ANY CONTRIBUTION HELPS US IN BUYING, PRESERVING AND DISPLAYING THESE HISTORICAL EXHIBIT ITEMS

CONTRIBUTE AS LITTLE AS $1, $5, $10, OR ANY AMOUNT

CLICK TO DONATE NOW

Notes:

- Howard H. Buffett, “State Department Meetings,” 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 9, 1947, 6621, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-13-2.pdf ↩

- Howard H. Buffett, “State Department Meetings,” 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 9, 1947, 6621, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-13-2.pdf ↩

- Ted Lipien, “First VOA Director was a pro-Soviet Communist sympathizer, State Dept. warned FDR White House,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 5, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “Stalin Prize-winning Chief Writer of Voice of America News, Cold War Radio Museum, March 12, 2019, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stalin-prize-winning-former-chief-writer-of-voice-of-america-news/. ↩

- Ted Lipien, Stefan Arski: Agent of Communist Collusion at VOA, Cold War Radio Museum, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/stefan-arski-agent-of-communist-collusion-at-wwii-voice-of-america/. ↩

- The bipartisan Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, also known as the Madden Committee, said in its final report issued in December 1952: “In submitting this final report to the House of Representatives, this committee has come to the conclusion that in those fateful days nearing the end of the Second World War there unfortunately existed in high governmental and military circles a strange psychosis that military necessity required the sacrifice of loyal allies and our own principles in order to keep Soviet Russia from making a separate peace with the Nazis.” The committee added: “For reasons less clear to this committee, this psychosis continued even after the conclusion of the war. Most of the witnesses testified that had they known then what they now know about Soviet Russia, they probably would not have pursued the course they did. It is undoubtedly true that hindsight is much easier to follow than foresight, but it is equally true that much of the material which this committee unearthed was or could have been available to those responsible for our foreign policy as early as 1942.” The Madden Committee also said in its final report in 1952: “This committee believes that if the Voice of America is to justify its existence, it must utilize material made available more forcefully and effectively.” A major change in VOA programs occurred, with much more reporting being done on the investigation into the Katyń massacre and other Soviet atrocities, but later some of the censorship returned. Radio Free Europe (RFE), also funded and indirectly managed by the U.S., never resorted to such censorship, and provided full coverage of all communist human rights abuses. See: Select Committee to Conduct an Investigation and Study of the Facts, Evidence and Circumstances of the Katyn Forest Massacre, The Katyn Forest Massacre: Final Report (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1952), 10-12. The report is posted on the National Archives website: https://archive.org/details/KatynForestMassacreFinalReport. ↩

- Howard H. Buffett, “State Department Meetings,” 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 9, 1947, 6621, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-13-2.pdf ↩

- Howard H. Buffett, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 1 (January 3, 1947 to February 24, 1947), January 24, 1947, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt1/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt1-16-1.pdf. ↩

- Howard H. Buffett, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12 (June 13, 1947 to December 19, 1947), “Is the State Department, Like Communists, Allergic to Free News Coverage?,” June 16, 1947, A2912, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt12/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt12-1.pdf. ↩

- Howard H. Buffett, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12, “Is the State Department, Like Communists, Allergic to Free News Coverage?,” June 16, 1947,A2912. ↩

- Francis P. Bolton, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 9, 1947, 6622, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-13-2.pdf ↩

- Francis P. Bolton, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 9, 1947, 6622, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-13-2.pdf ↩

- Adolph J. Sabath, 90 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 90, Part 9 (March 23, 1944 to December 19, 1944), A1521. ↩

- “Voice of America” name was not then yet commonly used. In the documents attached to Sumner Welles’ secret memo to the White House, John Houseman was identified as one of Office of War Information employees. ↩

- Ted Lipien, “April 1943 – State Department Warns White House of Soviet Influence at Voice of America,” Cold War Radio Museum, May 4, 2018, http://www.coldwarradiomuseum.com/state-department-warned-fdr-white-house-first-voice-of-america-director-was-hiring-communists/. ↩

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, The White House Years: Waging Peace 1956-1961 (Garden City: Doubleday & Company, 1965) 279. ↩

- Adolph J. Sabath, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 6, 1947, 6545, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-12-2.pdf ↩

- Adolph J. Sabath, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 6, 1947, 6545, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-12-2.pdf ↩

- Karl E. Mundt, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 5 (May 21, 1947 to June 11, 1947), June 6, 1947, 6550-6551, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt5-12-2.pdf ↩

- John Taber, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12 (June 13, 1947 to December 19, 1947), 6965, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6-2-2.pdf. ↩

- John Tabor, 93 Cong. Rec. (Bound) – Volume 93, Part 12 (June 13, 1947 to December 19, 1947), 6965, https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1947-pt6-2-2.pdf. ↩

Add Comment